I research American politics with a special focus on how citizens relate to the political parties. Some of my current projects study how polarized electorates can change the way politicians act, and how ordinary citizens respond to living in highly polarized contexts.

Below, you can see previews of projects in the works, and I have also posted links to my published articles.

Thank you for your interest!

In the Works

Affective Polarization and Legislative Behavior: Does Citizen Heat Meet with Elite Red Meat?

Over the past 40 years, US partisans have grown increasingly disdainful of the other party, but to what extent has this impacted elite-level politics? Recent research suggests that the consequences of affective polarization are largely “horizontal,” harming relations among the public, without changing how people relate “vertically” to government. In this article, I present evidence that citizen polarization can affect elite-level politics by encouraging elites to use more adversarial rhetoric. My analysis draws on 381,000 survey responses to estimate polarization by district from the 111th to 117th Congresses (2009-21), and on 167,000 e-newsletters and 4.7 million tweets to measure legislator rhetoric over that time. A variety of time-series cross-sectional models show a positive relationship between how polarized a legislator’s partisan base is, and the extent to which they employ the language of intergroup conflict. This rhetoric in turn reduces productivity and bipartisanship in Congress; however, that effect is small enough that pass-through effect of polarization is likely minimal. These results paint a nuanced picture of affective polarization’s role in modern US politics. While there are limits to its effects, affective polarization has nevertheless shaped the tenor of American political discourse so far this century.

Affective Polarization across Time and Place in the United States

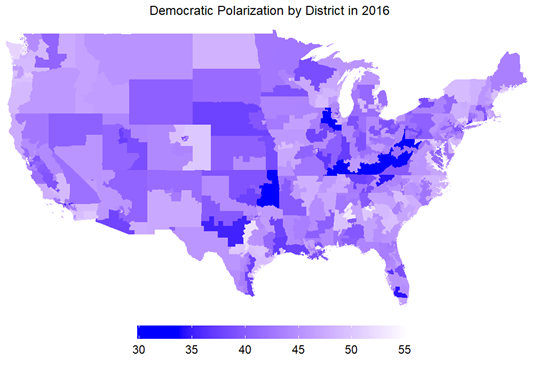

Affective polarization research has primarily focused on people who are polarized. However, most citizens do not harbor any deep partisan animosities. Have they therefore been unaffected by contemporary polarization? In this article, I reconceptualize affective polarization not just as a trait of individuals, but of contexts and electorates as well. To that end, I develop a dataset that estimates polarization at the state, US House district, county, and municipal levels of government from 2009 to 2023. These datasets show the wide variation in polarization as it exists across communities in the United States. In some places, politics takes on live-and-let-live tenor, whereas others feature intense partisan animosity. Exploring the descriptive predictors of this variation, I show that places that are older, more Internet-connected, and in politically competitive areas tend to be more polarized. From there, I use the data to show how studying polarization across time and place can allow scholars to link it to other concepts that define the current era. Drawing on insights from social identity theory and three-wave panel data from the 2010-2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Study, I show that in times and places of greater animus, people whose social identities align with their partisanship double down on their partisan identity, while those who are not as “well sorted” draw back.

Protest in a Polarized America

In the United States, partisans are more likely to protest than other citizens. This study compares the relative strength of two explanations for why. One contends that partisanship, as a group identity, may lead people to protest in support of their party’s interests. Another suggests that partisans may perceive a greater threat from the opposing party’s actions, leading them to protest more in response. Drawing from research on affective polarization, this study favors the threat-based explanation. Three studies of surveys fielded between 2014 and 2022 highlight the link between partisan animosity—or hostile feelings toward the opposing party—and protest participation. Studies 1 and 2 use panel data to show that citizens who hold greater partisan animosity at one point are more likely to report having protested in the years to follow. This effect on participation is comparable to that of their concern about the issues being protested. Study 3 further shows that protest participation is more common in communities where partisan tensions run high. Meanwhile, across models, the individual-level effect of partisan identity on protest was null or negative. These findings point social movements researchers toward threat-based explanations of how partisanship motivates protest and highlight an additional dimension to the relationship between partisan animosity and political participation.

Whose Party is This? Explaining Perceptions of US Party Ideology

Ideology and partisanship work reciprocally in the public mind, with citizens aligning their partisanship to their ideology and vice versa. However, parties exist in multiple forms—in the electorate and at different levels of government—and it is unclear which of these most informs the way that citizens perceive them ideologically. This study uses a multi-verse analysis of 960 models to observe how citizens’ ideological placement of the parties varied from 1990 to 2020 as a function of party ideologies in Congress, state legislatures, and the electorate. Citizen perceptions are influenced by federal parties, while the effect of state-level parties is negligible. Perceptions are also strongly impacted by how citizen-level partisans describe their own ideology, which carries mixed implications. On one hand, partisan-ideological sorting in the electorate has made it easier for voters to see the difference between parties. On the other, it leads voters to see the parties as being more extreme than they would otherwise. These findings underscore the extent to which parties, beyond their governmental function, are social groups with norms that are fluid, identifiable, and politically impactful.

Election Outcomes and Affective Polarization in the United States: A Regression Discontinuity Design (with Joseph Phillips)

Do election outcomes lead to affective polarization? A growing set of studies pose this question, fearing that the fundamental mechanism of democracy—competitive elections—may also pose a risk to its stability. However, many political stimuli occur around election time. How can researchers isolate the effect of winning or losing itself? In this study, we use a pre-post regression continuity design (RDD) to study the effect of close US House, Senate, and state-level presidential outcomes between 1996 and 2020 on the attitudes of survey respondents who experienced them. When controlling for pre-election polarization, people whose party saw a “close win” emerge more polarized than their opposition. However, this is primarily because of movement among the election’s losers, who depolarize by feeling less warmly toward their own party. If election losses weaken people’s commitment to democracy, anger at the opposition may not be the reason.

Analyzing Public Support for School-Based Mental Health Services (with Nicholas Hemauer)

Public schools play a central role in addressing the mental health crisis among American youth, but most schools are limited in the services they provide. As of 2019, 44 percent of administrators cited concerns about the public’s reaction as an obstacle to expanding these services. This article provides the first systematic accounting of public support for mental health services in schools. Specifically, we conduct two analyses. The first draws on observational data from three national surveys to study the individual-level characteristics that are associated with support for these programs. We find that among Americans, parents, women, racial minorities, younger people, and Democrats are more supportive of school-based efforts to improve mental health. The second uses a conjoint experiment, which randomly varies details of a proposal at a hypothetical school board meeting to identify the programs, policies, and contexts that are most likely to gain the public’s support. We find that school mental health services receive more support when they are funded via state as opposed to local taxes, and when parental permission is required to participate. These results of our study offer valuable guidance for policymakers, revealing high overall support for school mental health services, while highlighting key factors that may facilitate their implementation and acceptance.

Published Research

Toward an Ideological Common Space: Extending Bonica’s CFscores to the Citizen Level [read here]

Bonica’s (2014) campaign finance-based ideology scores, or CFscores, create an ideological common space that allows researchers to compare a wide variety of actors. Because relatively few citizens donate to candidates, however, the public is not well represented in this common space. This paper addresses that gap. It uses random forest machine learning on data from the 2012 Cooperative Congressional Election Study to impute CFscores for respondents who did not donate to candidates, based on how their policy views compared to those who did. These new scores are robust to differences in issue importance between donors and non-donors, and they outperform other ideological measures in predicting vote choice. The scores are then applied to a substantive exercise. Past research shows that extreme candidates for governor are penalized more by voters than those in lower-profile races. The implied mechanism—that vote choice for governor is more ideologically-driven—can be directly tested with imputed CFscores, since they uniquely allow comparisons between voters and candidates across races. An analysis of voting behavior in 2012 confounds expectations. Ideology appears to factor no more into vote choice for governor than for US House. These novel findings underscore the value of extending CFscores to non-donating survey respondents, and while current efforts are limited by data availability, this study offers encouragement and a roadmap to that end.

Measuring Executive Ideology and its Influence [read here]

Executives are important elites, and ideology is important to elite behavior, but measurement challenges and a focus on the presidency have kept scholars from fully exploring executive ideology. This article advocates studying US governors to learn more about executive ideology, and it encourages this work in three steps. First, I provide a critical overview of sources of data that scholars can use to measure gubernatorial preferences. Campaign finance-based ideology scores (Bonica 2014), or CFscores for short, offer the greatest data coverage and allow common-scale comparisons with other actors. Second, I address concerns that CFscores are unable to differentiate between members of the same party. I find that they amply explain within-party variation in other measures, as well as predict the decisions that governors make when in office. However, it does appear that CFscores are stronger indicators for Democrats than Republicans. Finally, I run a preliminary test of the substantive importance of studying executive ideology at the state level. Four models explain state policy liberalism as a function of executive, legislative, and citizen ideology. Gubernatorial preferences emerge as most predictive of the three. Taken as a whole, this article aims to substantively encourage and methodologically facilitate greater investigation into the role of executive ideology in the policy process.

Analyzing Attention to Scandal on Twitter: Elites Sell what Supporters Buy [read here]

Scandal has been described as socially constructed, in that some combination of the public, the media, and the political elite agrees that a transgression has occurred. This study is among the first to directly observe the “scandal as a construct” premise, using time-series data to estimate how each group’s attention to scandal affects that of every other. These data, collected from Twitter by Barberá et al. (2019), measure the daily tweet volume of media outlets, Members of Congress, and samples of the public in relation to four Obama Administration scandals. Granger causality testing and impulse response functions show, as expected, that a jump in scandal-related tweets by one group affects the tweet volume of every other. But the groups wield unequal influence. Over the long-run, elites drive their supporters’ attention to scandal more than vice-versa. However, in two of the four scandals, the opposite effect was seen in the short-run, opening the possibility of a “sounding board” effect where elites are responsive to the initial reactions of their supporters but lead the conversation thereafter. These results encourage further study into how short- and long-term information flows differ, and why groups may lead in some issue areas but follow in others.

A Potential New Front in Health Communication to Encourage Vaccination: Health Education Teachers (with Eric Plutzer) [read here]

Childhood vaccination rates have fallen below the level required for herd immunity. We assess the potential for a new channel by which to communicate the importance of immunization: the nation’s health education teachers. We first conduct a content analysis of the curricular standards that govern health education in each state reveals. We find that only 12 states require any discussion of vaccines, and that none provide detailed guidance on how teachers can help young adults make wise immunization decisions. We also present results of the first, nationally representative survey of middle and high school health teachers to ask about vaccinations. Only 42% of teachers discuss the benefits of vaccination and immunization in their classes, but very few (2.4%) are classified as “vaccine skeptics,” and almost all (97.4%) report that they are responsive to state curricular standards. These results suggest that curricular changes can effectively mobilize health teachers to share scientific information about vaccines and immunizations, and thereby improve collective health outcomes.

PhD Stipends and Program Placement Success in Political Science (with Dominik Stecula) [read here]

A key grievance of the student labor movement is that across much of academia, and especially in the social sciences and humanities, stipends tied to PhD assistantships fall short of a living wage. In this article, we consider the issue from a pedagogical perspective, expecting that higher pay may lead to stronger program outcomes. We collect and validate data on assistantship stipends in political science from PhDStipends.com, and on tenure-track placements from an analysis of departmental placement pages. Graduate pay is significantly associated with tenure-track placements in the job market cycles spanning 2019-2021, independently of program size, rank, student unionization, location, and institution type and endowment. Across model specifications, a $5,000 increase in student pay corresponds with 2.7 more placements per 100 enrolled students (or 34% of the median rate) over this period.